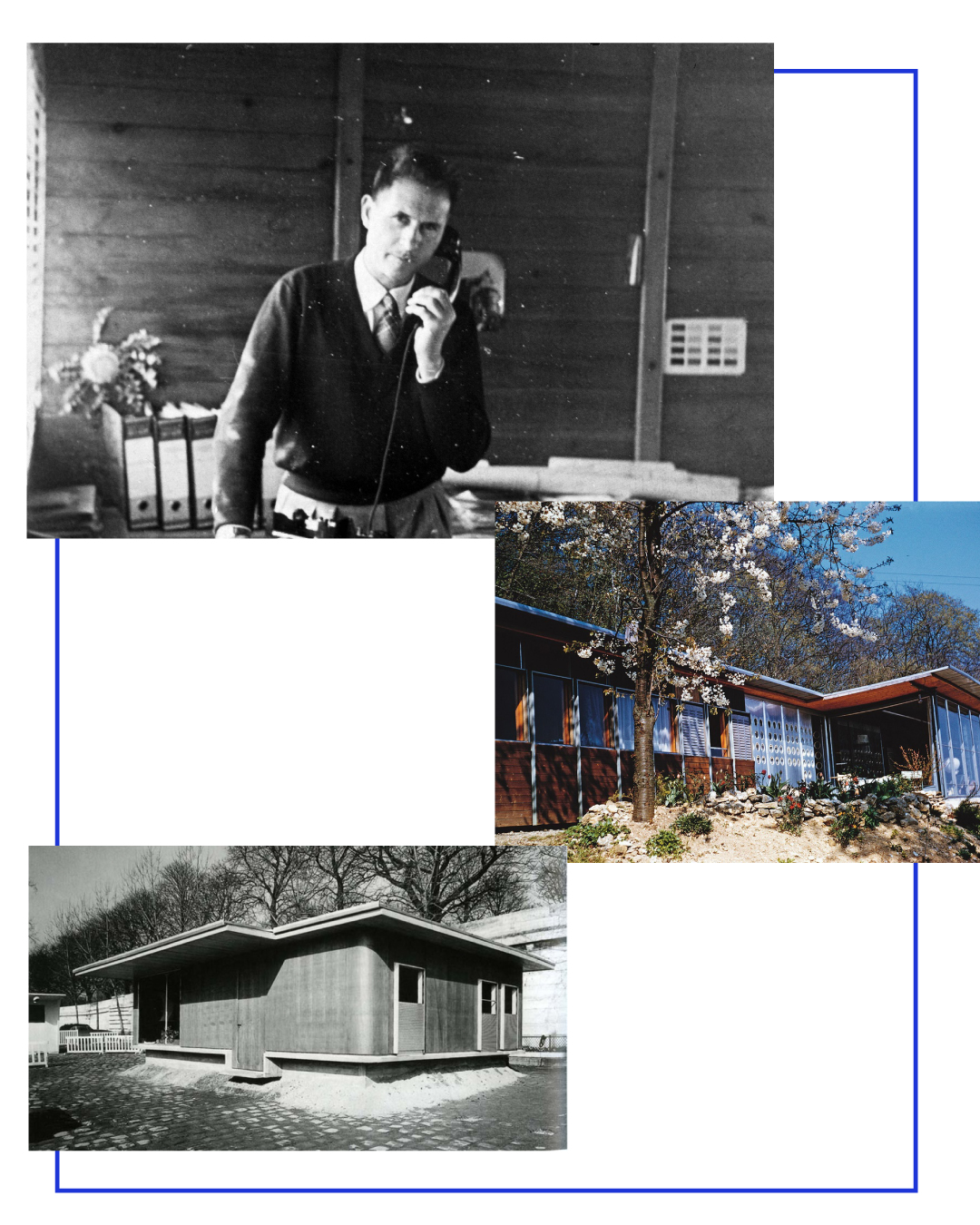

Jean Prouvé (Paris, 1901 – Nancy, 1984) is considered by many to be the “guru of French midcentury modern”. In 1924 he finished his training as a metal craftsman. Since then, he became part of the generation of “optimistic” creators who believed in scientific and technological development as the solution to the problems of the modern world. He would make that clear when he signed up as a member of the Union of Modern Artists (“We like logic, balance and purity”) invited by Le Corbusier. Prouvé also came from a family of artists. His father, Victor Prouvé was a painter, sculptor and engraver, member ofs École de Nancy, an art nouveau movement that tried to unify art and manufacturing and make it accessible to the masses.

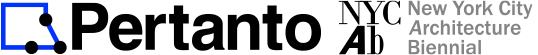

In 1931 he came into contact with the modernist movement and began an architectural journey that would make him a pioneer of the prefabricated concept. In the late 1930s Prouvé designed the BLPS Weekend House, a prototype of detachable housing that he devised to be assembled and easily movable by the users to their vacation destinations. This design would make way, with the outbreak of World War II, to its use into military barracks.

At the end of the war, the French government commissioned him to design a series of refugee houses, for which he developed the production of prefabricated housing and furniture. He created new construction systems, encouraging on-site assembly with parts previously manufactured in the workshop, as opposed to the traditional way. His aim was to produce quality housing and furniture designed for collective facilities without losing his avant-garde character. For Prouvé, there was no difference between the construction of a piece of furniture and the construction of a house; he believed that industrialization was only possible with a reduced number of components.

He founded his own factory in the town of Maxeville in 1947, where he produced some of his most emblematic furniture: the Guéridon (1949), Compass and Granite (1950), the Antony chair (1954), the Bahut cabinet (1951) and the furniture for the Air France offices in Brazzaville. He was also able to mass-produce some of his earliest works: the Standard chair (1934), the Cité (1930) or the Rayonnage bookcase (1936), aeronautical technology with a handcrafted look. In the Maxeville factory, he placed four fundamental values at the helm of architecture and design that extended throughout his work: economy, functionality, resistance and comfort. In 1953, due to disputes with shareholders, he closed the factory; since then, he devoted himself to nomadic architecture, as well as working as a consultant and teacher.

Using his innovative methods, he built the Tropique House (1949), the Métropole House (1950) and the Coque House (1951) which, as a novelty, was assembled from curved roof panels with metal supports. Prouvé always designed his houses together with their corresponding furniture, to create a synergy between comfort and functionality.

Among his most significant collaborations to modern architecture is the Light Facades System he created in 1957, the result of previous studies,whose main element is the aeration and easy acclimatization of these facades, solving acoustic and thermal insulation issues. In the same way, in 1960, he developed two important manufacturing systems: the reticular roof with variable surface, which adapts to all types of reconstruction, and the Tabouret, a system that puts in place two elements: post and beam.

His own house, the Maison du Coteau (1954) in Nancy, is considered an emblematic work of contemporary architecture, built from recovered elements (“elle est faite de bric et d’broc”) said Prouvé himself, referring to the fact that it was made with what he had found at the Maxeville factory. During this period he also built the Pavilion of the Centenary of Aluminum, installed at the Quai d’Orsay in Paris, which can be completely dismantled and is considered, by some, to be his masterpiece.

Another emblematic work is the Les Jours Meilleurs House (1956), a project he undertook at the request of the government in response to the massive deaths of homeless people during the winter of 1954 in France. Prouvé devised a house of approximately 50 m2, industrially manufactured and assembled on site, equivalent to a two-bedroom apartment. Unfortunately, the model did not receive the required technical approval, which prevented its industrial production, and only five units were manufactured in the end. During the same period he designed houses for the desert colonies (Sahara House, 1958) and participated in the construction of the Freie Universität in Berlin (1963-1971).

There is no doubt that Jean Prouvé is a pioneer of 20th century furniture and housing production, he collaborated with great architects of his time and established new practices that became an industry standard. It is indisputable that it was Prouvé who introduced the concept of sustainability and social design into his housing, forever permeating the history of design and construction.

“I have the impression that my father did not consider himself an artist. He always repeated to us: I am not an engineer, not an architect, I am a man who works in a factory,” said Catherine Prouvé in an interview about her father’s work for Vitra, which, to this day, continues to produce Prouvé’s iconic furniture that revolutionized post-war aesthetics thanks to its unusual juxtaposition of industrial and artisanal techniques

Leave A Comment